The Tetrad Trade-Off Principle:

Chanimetal Self-Propelling Barge Construction Project

Art Madsen, M.Ed.

A detailed analysis of two conflicting project management strategies in Equatorial Africa is presented in this article, within the context of a multi-million dollar 70-meter barge construction project on the Congo River. Belgian-trained Congolese Shipyard Management personnel were ‘compelled’ to cooperate with an American-led Consortium, under a temporary Joint Task Force sub-contract arrangement. Labor problems erupted in the fourth month as a result of fundamental violation of the Tetrad Trade-Off Principle. Timely resolution of the impasse was proposed by American Management and the barge construction project was completed ‘on schedule and at cost’, but only due to certain fortuitous factors.

INTRODUCTION

As a former relatively high echelon managerial employee of the Inga-Shaba Transmission Line Consortium, I have at my disposal copious cost data and basic descriptive information concerning this major construction project in the Central African nation once known as Zaire, today the Democratic Republic of Congo. Within the framework of one of the Inga-Shaba Line's sub-contracts, I would like to share at least a portion of my data and insight with you.

The entire Inga-Shaba project, costing more than one billion USD, was originally conceived in 1973 and completed in 1984. The present report cannot, of course, validly discuss the entire range of activity associated with such a mega-project, America’s largest undertaking in the 1970s and 1980s in Africa. However, there were a number of relatively small scale sub-contracted tasks nestled within the 1700 kilometer Inga-Shaba Extra High Voltage D.C. Transmission Line project which could be beneficially analyzed in a brief report such as this. I have selected one such sub-contracted project.

Unprecedented amounts of tower steel, supplies and heavy equipment had to be transported deep into the interior of the Democratic Republic of Congo during the construction phase of the Inga-Shaba Line. The Congo River, the world’s second largest, served as the primary route for moving materials into the heart of this remote and logistically challenging equatorial nation. No barges capable of transporting 20-ton transformer units upriver were available. All existing river craft were for shipment of food, passengers or light freight. Complicating matters, cataracts blocked the Congo River at a point approximately 150 miles from the Atlantic, necessitating transhipment from the Port of Matadi to Kinshasa by train. Once goods were in Kinshasa, they could be loaded onto riverboats for further shipment into the country’s Interior. This situation is displayed clearly on Appendix D.

Obviously, no pre-constructed barges could be brought to Kinshasa due to the non-navigability of the river at the point of the cataracts. New vessels, as the Belgians realized since the earliest days of their colonization, had to be constructed on-site in Kinshasa.

Among Inga-Shaba Project Managers, there was never any serious discussion about whether or not to build these barges. No rail systems leading directly into the Interior of Zaire were available; and, of course, there were no roadways through the jungle and savanna lands over the complete distance of 1700 km. Although the KDL (Kinshasa-Dilolo-Lubumbashi) rail link through portions of Angola was theoretically available for shipment of the 20-ton transformers to Lubumbashi and on to Kolwezi, hostile rebel activity in Angola precluded use of the KDL line. Thus, given logistical considerations, vast sums of money had to be expended to ship the transformers upriver to Ilebo, and then to Kolewzi by an existing rail line traversing a portion of the jungle.

"Pay back, net present value and internal rate of return" were not operative concepts on the barge subcontract since all Inga-Shaba expenses and funding were guaranteed by the institution of "last resort", EXIMBANK and the US Treasury. This blanket guarantee encouraged, it is fair to state, wasteful and improperly controlled expenditures as well as lax planning strategies.

Ultimately, the overall Inga-Shaba project was evaluated in terms of "pay back", of course, by the Government of Zaire in the long run, which hoped to settle all international loans during the 21st Century through the sale of electricity. But the barge sub-project, as such, was not singled out for financial analysis, other than to ensure that the jointly approved 2-barge budget was honored. Interestingly, Chanimetal had no viable competitors able to produce such large and sophisticated barges anywhere in the Republic.

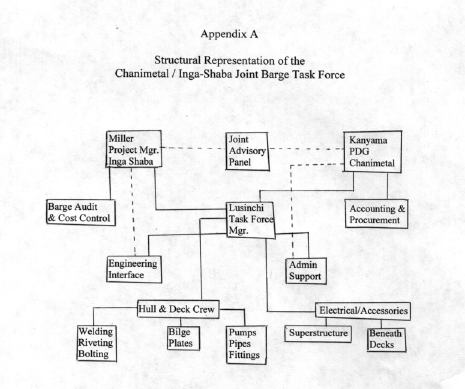

Inga-Shaba Project Management, selected from among existing administrative personnel of the Consortium’s Lead Partner, Morrison-Knudsen International (MKI), contacted the largest ship-builders available, Chanimetal. This firm was essentially the legacy of the Belgians, but its leadership in 1980 had become Congolese, or Zairian, under the post-independence government of President Mobutu Sese Seko. Its President-Director-General, Mr. Kanyama, was a university graduate, an astute engineer, and an accomplished businessman. On the Inga-Shaba side of the equation, management consisted of engineers and administrators from Boise, Idaho, employed by MKI. See Appendix A for a Structural Representation of the Joint Barge Task Force.

SCOPE AND OBJECTIVES

The purpose of this analytical report, within the context of the above scenario, is to explore the primary project management strategies utilized by the joint Amero-Zairian Inga-Shaba/Chanimetal task force assigned to construct, within tight deadlines, two 70-meter self-propelled barges for transhipment of heavy equipment from Kinshasa to Ilebo along the Congo River in 1981. Project objectives, planning and control systems utilized at that time will be reviewed and further elucidated by appended charts. Members of the management task force, and their respective PM approaches, will be discussed, as will the efficiency of their strategies in terms of costs, scheduling and optimization of manpower. At least one problematic development and its timely solution will also be analyzed.

Casting a glance retrospectively over our shoulder, the now well-established PM principle referred to in the literature as the Tetrad Trade-Off concept will form the unifying theme of this paper, particularly within the context of the Inga-Shaba/Chanimetal task force. The four prongs of this principle are the key variables of (1) scope of product, (2) quality grade, (3) time-to-produce and (4) total cost-at-production. All of these criteria were, of course, both vital and operative factors, to varying degrees, during construction and testing phases of the two self-propelling river barges.

The "trade-off" among these four parameters involves the idea that, assuming one side of an imaginary four-sided frame with moveable joints is solidly anchored, one other parameter can be moved, as desired, but only by affecting the remaining two sides. It is obvious, for example, that if quality and scope are to be positioned desirably, then cost and completion-time are impacted. All four of these project criteria must be consistent and realistically feasible, and in balance, otherwise "success" is not likely to be achieved as defined by either the client or constructor (Wideman, Jan. 2000). Further mention will be made [in this paper’s assessment and critique section] of the consequences of misapplication of this important tetrad trade-off principle.

This analysis will view the Chanimetal/Inga-Shaba 70-Meter Barge construction schedule with these notions in mind, demonstrating through graphics and descriptive assessment how this Joint Task Force managed completion of the five-month project on schedule and well within contractually approved costs. This was achieved in spite of a lengthy labor dispute that threatened to upset the original construction schedule and manpower distribution projection. Necessarily, there will be some simplification of data to demonstrate key conceptual points introduced in class lectures.

THE PROJECT

The sub-contract for completion of two 70-meter self-propelling barges called for their completion in a period of five months, within a budgetary ceiling of 3.5 million USD, fully equipped with living quarters for the crew, massive engines, and all accessories. Disbursements were made upon submittal of periodic "project status reports" and physical verification by Inga-Shaba Management of work accomplished.

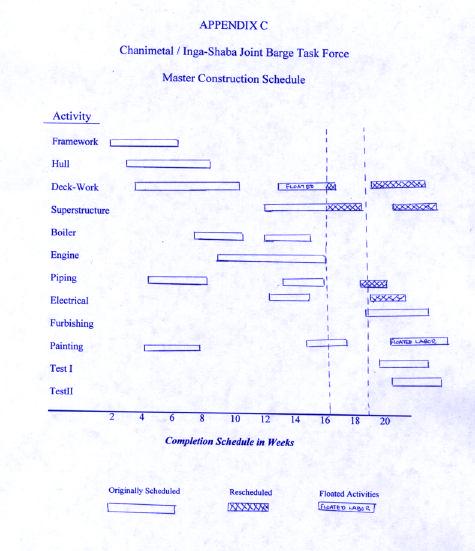

Chanimetal had three dry-docks, two of which were occupied. However, one of the two vessels then under construction for another Chanimetal client was to be completed and launched within only 10 days. Construction of Inga-Shaba’s barges, therefore, could be begun simultaneously on the two available dry-docks. All figures and data in this report reflect on-going costs and work for both barges. The principal problem anticipated by Chanimetal in construction of these extra-large barges was obtaining, from European or US sources, required steel plating and pipe-work for both of them on schedule. Fortunately, except for the hull and deck-work (obviously not tasks that could be "floated" to another position on the master schedule) many of the engine room and boiler sector tasks could be repositioned on the time-continuum, as noted on the Flow Chart in Appendix C. Stated in other terms, if certain parts or materials were delayed in shipment from abroad, installation of them could be floated to new positions on the completion schedule.

Manpower requirements were enormous inasmuch as unskilled labor in the Congo is virtually non-productive. Average wages were, and are, so low as to discourage performance. Portrayed below, on Figure 1, are rough wage scales for the period in question.

LABOR CATEGORIES AND WAGE SCALES IN THE REPUBLIC OF ZAIRE 1980 TO 1983

Labor Category / U.S. Monthly Salary Equivalent

Laborers (Unskilled to Skilled)................$11.00 to $45.00

Supervisors (Low to High Echelon)...............$30.00 to $65.00

Administrative (Non-Degreed to Degreed).........$40.00 to $150.00

[Source: Inga Shaba Project Data, 1980-83]

Figure 1

With the Zairian equivalent of only 11 USD per month as an incentive, unskilled manpower served limited purposes and generally performed heavy labor tasks, doing so only when prodded. Semi-skilled laborers were somewhat more useful since their novice construction experience in a variety of fields had been demonstrated on previous shipbuilding projects. Skilled laborers were welders, boilermakers, pipe-fitters, electricians, and so forth, all highly valued workmen. There were also Supervisory (Maitrise) and Administrative (Cadre) employees, but very few.

It is perhaps shocking to note that these wage scales are so low by the industrial standards of most western nations. Labor was not in demand in Zaire; indeed, it was an employers' market. The 3.5 million dollar sub-contract total for both barges reflected mostly the costs of materials, parts, technical support and supervisory personnel. Only about 4% of that sum was reserved for indigenous labor. The Joint Task Force was aware of this factor, but, under standing wage and labor regulations in Zaire, could do little initially to alter the situation.

MANAGEMENT AND PLANNING STRATEGIES

The Joint Task Force was divided in its approach to utilization of manpower. The Belgian-trained Congolese managers preferred to maintain the low-wage, high disciplinary pressure approach, reminiscent of 19th Century Taylorism, whereas the American managerial contingent favored liberal wage and benefit policies with incremental incentive increases. In the first three months of the project (April, May, June 1981) the Congolese methodology was used. This resulted in considerable shipyard tension among workers who were only marginally able to maintain the stiff pace indicated on Appendix C, as called for by the Joint Task Force. Dissatisfaction was rife. In early July, labor unrest resulted in a 3-week strike (‘industrial action’) paralyzing all levels of shipyard labor. Staffing dropped to minimal levels and building progress was adversely impacted. Appendix C shows the rescheduling of essential tasks, notably the completion of deck-laying, which resulted from the strike, at considerable cost in terms of time and money. Due to implementation of American managerial, incentive-based policies – notably (1) settling the strike amicably through astute bilingual translation and (2) offering a dramatically improved wage and benefit package (more than a 22% overall increase) -- workers began to respond positively, became eager to perform, and pre-strike productivity levels rose, after actual strike settlement, significantly.

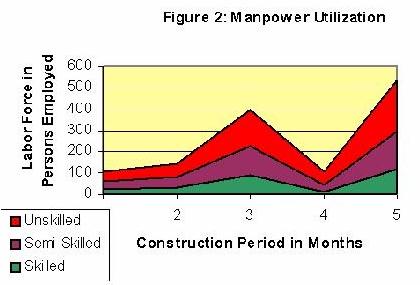

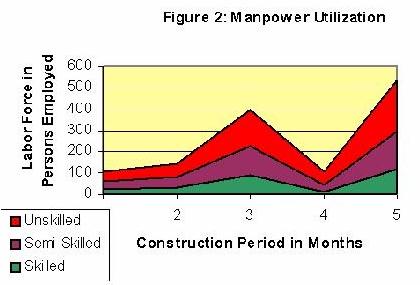

New supervisory methods were initiated in late July under American command. Figure 2, below, demonstrates the pattern of manpower utilization on a monthly basis showing the gradual build-up in the 3-months prior to the strike (under Congolese management), the sharp decline during the strike, and the necessary, but artificially high manpower levels (under American management) following the labor disruption.

Several observations can be derived from Figure 2, and from barge construction records still partially available at Chanimetal, ... not to mention my own records. Daily use of manpower was consistent throughout the month, pre- and post-strike. Weekly fluctuations did not take place; however, there were holidays and week-ends as in any western nation. The seemingly high number of employees on the graph reflects the fact that two shifts of workers were employed, 16 hours per day, on both barges. Under these circumstances, Figure 2 portrays with considerable accuracy the deployment of manpower for all three skill-levels noted. It is useful to recall that most productivity and "value-added" work was accomplished by the skilled worker category, although these types of employees were relatively few in number, as can be seen.

Even though a concerted effort on the part of the Joint Task Force was made to ensure smooth and gradual build-up of manpower as the deadline approached, and as floated tasks became necessary to perform, the Task Force failed in this objective. Obviously, there were issues of labor unrest and unavailable materials that tended to foil the smooth operation of the originally drafted sub-contracts. Success was achieved, nonetheless, under the more liberal American policies, predicated on incentive and reward for services performed.

CONTROL SYSTEMS

On the Chanimetal Barge Project, there were a number of critical control functions that had to be enforced.

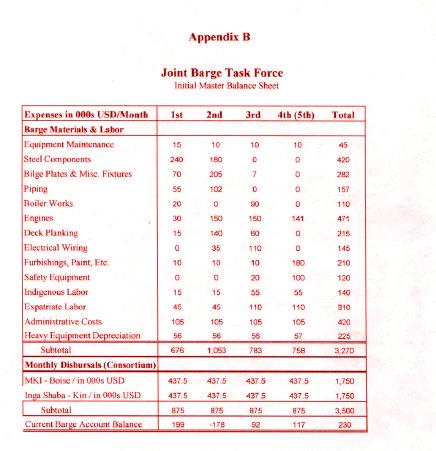

Surely, financial controls were monitored by a team of accountants, employed by Inga-Shaba and by Chanimetal, and, as disbursements were received, they and payroll personnel closely planned and reviewed expenditures. Appendix B displays the cash-flow patterns of the Barge Project from inception through completion. This Excel Chart, however, has not been adjusted to reflect the effects of the strike period, and, indeed, major departures from Appendix B did take place as the project neared completion, particularly in the fourth and fifth months. It became necessary to re-route certain funding from Inga-Shaba general accounts to the Barge Project to offset unexpected expenses, notably the 22% salary increase package awarded workers. In spite of this technical violation of ‘controls’, the Barge Project was still completed on time and under budget, due to over-estimation, by a factor of 12-15%, of other construction costs.

Management controls on purchasing of construction materials were largely in the hands of the Congolese who had historically established a variety of ‘out-sources’ for their shipbuilding materials. However, American standards for the barges had to be contractually honored and occasionally barge materials were purchased through Boise, Idaho, specifically with reference to the furbishing of crew quarters and safety equipment.

Cost overruns, which were relatively rare, were reviewed internally by the Joint Task Force and decisions were made on a case-by-case basis. From project commencement to the completion phase, there was, on balance, a smoothly implemented cash-flow policy, as long as bilingual Project Status Reports were submitted in a timely fashion and other contractual clauses in this regard were honored. The 4th month labor dispute unsettled matters somewhat, although compensatory mechanisms were put in place to deal with the consequences. Money was never a problem on this project; it flowed as required.

CRITIQUE AND ASSESSMENT

Throughout this review of several major parameters and policies pertaining to the Inga-Shaba/Chanimetal Barge Project, the Tetrad Trade-Off principle has not been highlighted primarily in order that PM principles elucidated in class work, such as manpower utilization, scheduling strategies and fiscal policies, could be briefly included in this analysis. However, the Tetrad Trade-Off work of Bing and Wideman (1994 and 2000), as well as the work of many of their predecessors in the field of Project Management, should not go unnoticed within the context of this specific project.

Because Belgian-inspired Congolese labor policies in effect during the first 3 months of this project clearly attempted, under some coercion from the American contingent, to place undue stress on shipyard workers who were already under-compensated, it is obvious that Tetrad Trade-Off was an operative factor in this delicate equation. Briefly, the "scope of the project" could not be changed; it was anchored. But an attempt to improve "quality" was being made, at the expense of time and cost, the other two factors. Excessive distortion of Wideman’s theoretical ‘jointed-quadrilateral’, described earlier, was occurring, and two corners were thrown out of alignment. The strike, otherwise avoidable delays and additional internal costs ensued. Fortunately, in the case of this sub-contracted barge project, money was no object and American expertise put things back into alignment. The barges were completed, christened and carried, for the first time in the history of man’s logistical feats on the Congo River, their two 20-ton transformers to Ilebo as foreseen. And they did so, due to extraneous factors unrelated to actual planning, at pre-determined cost.

REFERENCES

Bing, J. "Principles of Project Management", PM-NETWORK, PMI, January 1994, 40.

Burke, R. Project Management, 3rd Edition, Wiley, London, 1999

Devaux, S. Total Project Control: A Manager’s Guide to Integrated Project Planning, Measuring and Tracking. Wiley, New York, N.Y., 1999.

Kangari, R. Managing International Operations: A Guide for Engineers, Architects, and Construction Managers, ASCE Press, New York, 1997.

Laufer, A. Simultaneous Management: Managing Projects in a Dynamic Environment, AMACOM, New York, N.Y., 1997.

Lientz, B. Breakthrough Technology Project Management, Academic Press, San Diego, 1999.

Project Management Institute (PMI), A Guide to the Project Management Body of Literature, PMI, Upper Darby, Pennsylvania, 1996.

Rosenan, M.D. Successful Project Management: A Step by Step Approach with Practical Examples, Third Edition, Wiley, New York, N.Y., 1998.

Wideman R. "First Principles of Project Management", AEW Services, Vancouver, B.C., January 2000

This organizational chart is derived from the original 1981 structure of the Joint Task Force. Obviously, in the 1980s, organizational management had progressed to the stage where these types of inter-corporate models were fairly common. Preparation of such graphs was typically executed by draftsmen in the 1980s, rather than with MS Powerpoint or other graphic software available today.

Note the "Joint Advisory Panel which met weekly. Here, decisions regarding unusual developments such as cost overruns and strike activity were routinely made. Bilingual negotiations during the strike were conducted under the authority of the joint Advisory Panel.

Mr. Lusinchi reported to both Messrs. Miller and Kanyama on barge progress, and was responsible for initial compilation of the Periodic Status Report, re-edited, written and translated by the Chief Translator.

The tasks beneath Mr. Lusinchi’s level were related to the Work Breakdown Schedule (WBS) shown as part of Appendix C.

This Initial Master Balance Sheet for the Joint Barge Task Force does not technically allow for the 3 or 4 week delay attributable to the shipyard strike in July of 1981. It shows the first four months [originally scheduled on the Sub-Contract, but later changed for reasons unrelated to the strike] of the five ultimately required for completion of the two barges. The fourth month on this chart is actually the fifth, as noted, due to the strike. The entire impact of the strike is not visibly reflected on this initial master balance sheet, although the "bottom line" is, in fact, accurate.

Strangely, even though the strike was costly, the entire project fell well within budget, with a cash surplus of $230,000, in the Joint Inga-Shaba/Chanimetal Account at time of project completion. This was due to unintentional overestimation of certain items, notably steel components and heavy equipment depreciation. Some of this surplus was assigned to pay for indigenous wage hikes following negotiated settlement of the dispute. Still, "practically nothing" by Western standards, was actually spent on indigenous labor, as can be seen. Considerably more was spent on expatriate time (there were only a handful of foreign employees) and, of course, on barge construction materials which constituted the vast portion of the $3.5 million budget.

This Master Schedule, predicated on CPM thinking, is derived, in part, from the less complex Work Breakdown Schedule (WBS) sketched below. WBS Tasks B, C, E and F heavily determined the content of the Master Schedule. On the Master Schedule the disruption of progress, caused by a prolonged labor strike in the ‘16 to 18 week time slot’ is indicated in large part by the shaded tasks which had to be rescheduled. Floated tasks, such as some deck-work and piping installation, allowed other critical work (e.g. superstructure) to proceed, even during the strike. The final surge in shipyard activity is portrayed in the lower-right of the main chart; these tasks consisted notably of furbishing, painting and testing during the last 2 weeks.

Joint Barge Task Force Work Breakdown Schedule

ß Design and Engineeringà

A. Cost-Estimation B. Scheduling C. Personnel D. Task Force E. Materials F. Test Group G. Contingency

Below are two graphic representations of a typical task (painting) performed by a given number of workers in the final days of the barge project. The maximum number of painters, for both barges, is displayed, and the proportion of FLOATS required is also indicated. Beneath this diagram is a node-chart portraying the early starts, latest possible starts and duration of task among other critical factors.

Raw Information: Painting activities includedà (A) Cleaning surface (B) Application of Primer Coat (C) Application of Secondary Coat (D) Random Testing of Painted Surfaces (E) Application of Anti-Corrosion Chemical. Note: 20 Indigenous Painters were available for each barge, per shift. Total Painters: 80.

INSERT RESOURCE ANALYSIS CHART HERE

INSERT NODE CHART HERE

Appendix D. Map of the Congo

Transformer Routing Sequence à Matadi, Rail, Kinshasa, River, Ilebo, Rail, Kolwezi